The Eulogy

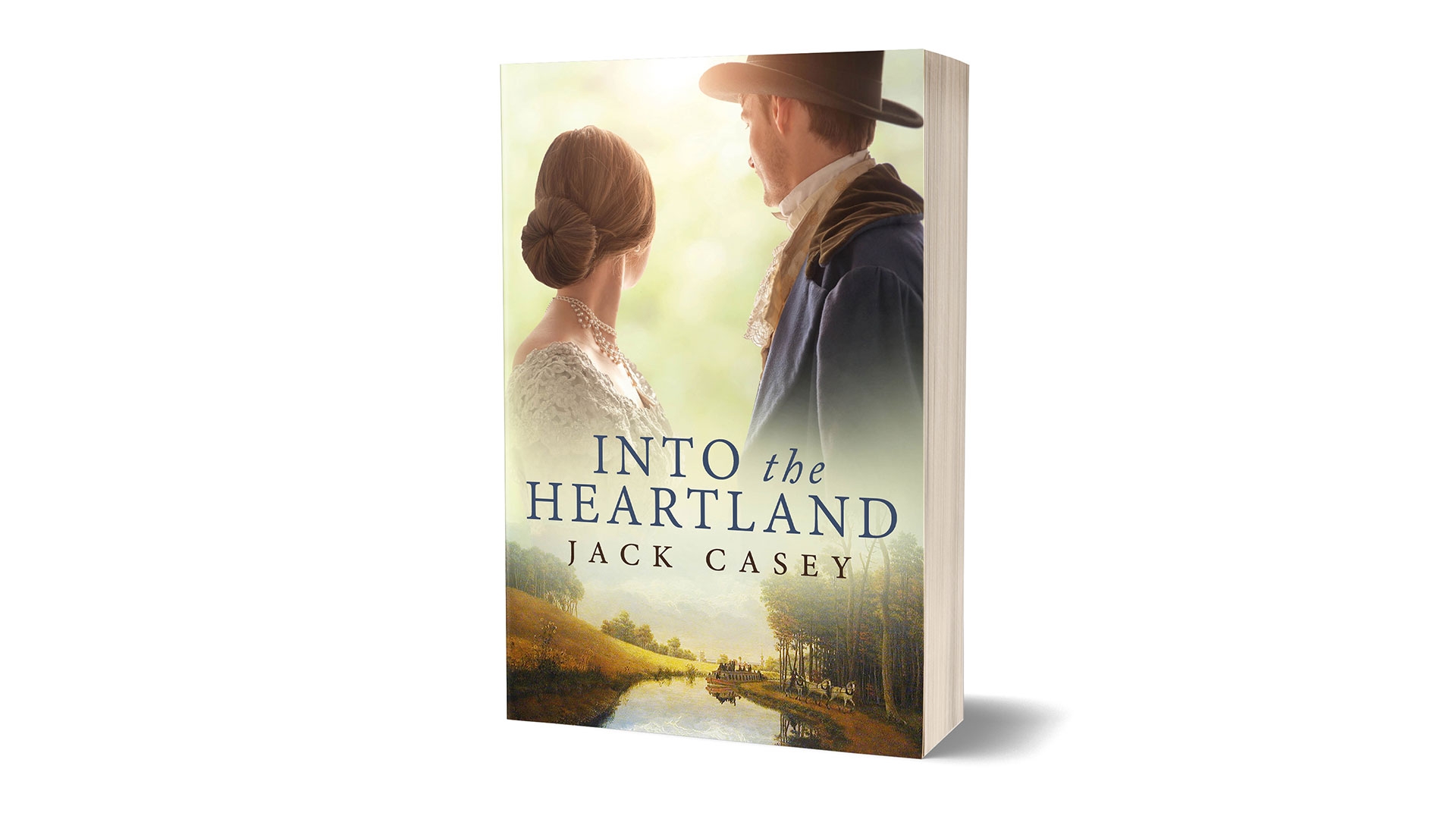

BUST OF GOUVERNEUR MORRIS

What would your best friend say at your funeral? Would he or she delve into those times of your life you’d rather hide? Or would they praise and glorify you because that’s what your friends and family want to hear?

This problem gets difficult when the deceased has lived a contentious public life such as Alexander Hamilton’s. When, on his deathbed, Hamilton asked his old friend to deliver his eulogy, Gouverneur Morris had a dilemma: what to say and more importantly what not to say.

Gouverneur Morris wrote the Preamble to the Constitution and was one of its signers. Like his bosom friend Alexander Hamilton, he believed in a strong centralized government and was “an aristocrat to the core.” Of the French Revolution, Morris wrote, “there never was, nor ever will be a civilized Society without an Aristocracy.” On the other hand, he supported absolute religious freedom, and he abhorred slavery.

Morris believed that the “common people” were incapable of self-government because the poor would sell their votes to the rich and therefore voting must be restricted to property owners. He retained a profound contempt for “democratic theories.”

Morris served as United States minister to France during the French Revolution (1789 – 1799), and he witnessed firsthand what an unleashed rabble could do. The rabid murderous mob in Paris threw Thomas Paine into prison and exiled Marquis de Lafayette after confiscating his estate and imprisoning his family. But when the mob came to lynch Morris, he took off his wooden leg and waved it high, claiming that he lost his leg battling for human rights in America. This was a ploy. He lost his leg in a carriage accident in 1780, but his ruse worked and he was spared.

MORRIS’S WOODEN LEG

Morris and Hamilton were soulmates, and though Hamilton was only three years younger, Hamilton called Morris “uncle.” When Morris heard Hamilton had been shot, Morris went immediately to his bedside, and ignored his own grief to help Hamilton’s wife Eliza through hers. At Hamilton’s request, he agreed to deliver the eulogy.

Morris knew that Hamilton could be prickly, and his wildly controversial life needed to be sanitized. He recorded his misgivings about the speech in his diary:

July 13, 1804 [the day after Hamilton’s death]: “Take Mr. Harison [Richard Harison] out to dine with me. Discuss the Points which it may be safe to touch tomorrow and those which it will be proper to avoid. To a Man who could fully command all his Powers this Subject is difficult.

“The first Point of his Biography is that he was a Stranger of illegitimate Birth. Some Mode must be contrived to pass over this handsomely. He was indiscreet, vain and opinionated. These things must be told or the Character will be incomplete—and yet they must be told in such Manner as not to destroy the Interest. He was on Principle opposed to republican and attached to monarchical Government—And then his Opinions were generally known and have been long and loudly proclaimed.

“His Share in forming our Constitution must be mentioned and his unfavorable Opinion cannot therefore be concealed. The most important Part of his Life was his Administration of the finances. The System he proposed was in one Respect radically wrong—moreover, it has been the Subject of some just and much unjust Criticism. Many are still hostile to it, though on improper Ground. I can neither commit myself to a full and pointed Approbation, nor is it prudent to censure others. All this must, somehow or other be reconciled.

“He was in Principle opposed to Duelling, but he has fallen in a Duel. I cannot thoroughly excuse him without criminating Colo. Burr which would be wrong and might lead to Events which every good Citizen must deprecate. Indeed this Morning when I sent to Colo. [William S.] Smith, who had asked an oration from me last Night, to tell him I would endeavor to say some few words over the Corpse, I told him, in Answer to the Hope he expresst that in doing Justice to the Dead I would not injure the living, that Colo. Burr ought to be considered in the same Light with any other Man who had killed another in a Duel, That I certainly should not excite to any Outrage on him, but, as it seemed evident to me that legal Steps would be taken against him. Prudence would, I should suppose, direct him to keep out of the Way. In Addition to all the Difficulties of this Subject is the Impossibility of writing and committing anything to Memory in the short time allowed. The Corpse is already putrid and the funeral Procession must take Place tomorrow Morning.…”

“July 14, 1804, A little before ten go to Mr. Church’s House from whence the Corpse is to move. We are detained till twelve. While moving in the Procession I meditate—as much as my feelings will permit—on what I am to say. I can find no Way to get over the Difficulty which would attend the Details of his Death. It will be impossible to command either myself or my Audience—their Indignation amounts almost to frenzy already. Over this, then a Veil must be drawn.

“I must not either dwell on his domestic Life—He has long since foolishly published the Avowal of conjugal Infidelity. Something however must be said to excite public Pity for his family which he has left in indigent Circumstances. I speak for the first Time in the open Air, and find that my Voice is lost before it reaches one tenth of the Audience. Get thro’ the Difficulties tolerably well—Am of Necessity short especially as I feel the Impropriety of acting a dumb Shew which is the Case as to all those who see but cannot hear me. I find that what I have said does not answer the general Expectation.

“This I knew would be the Case—It must ever happen to him whose Duty it is to allay the Sentiment which he is expected to rouse. How easy it would have been to make them for a Moment absolutely mad! This Evening Mr [William] Coleman Editor of The Evening Post calls. He requests me to give him what I have said. He took Notes but found his Language so far inferior that he threw it in the fire. Promise, if he will write what he remembers, I will endeavor to put it into the Terms which were used. He speaks very highly of the Discourse—More so than it deserves.”

NANCY CARY RANDOLPH

Always a lady’s man, Morris hired Nancy Cary Randolph as a housekeeper in his lavish mansion. Nancy had been implicated in the murder of a newborn from an illicit affair she conducted with her brother-in-law Richard Randolph. Randolph stood trial for murder of the infant but, defended by Patrick Henry and John Marshall, he was acquitted. Randolph died suspiciously three years later at his plantation aptly named Bizarre. His wife and her sister Nancy, his paramour, were also suspected of the murder.

When Randolph’s wife finally banished her sister from Bizarre, Nancy moved north and lived in boarding houses until Morris hired her. Morris was 57 and Nancy was 35 when they surprised relatives at a Christmas gathering by marrying. Nancy wore her housekeepers dress. They had a son who was his mother’s “richest treasure,” and mother and son lived together at the estate until Nancy died 21 years after her husband.

From many land speculations, Morris owned vast tracts of land in Northern New York State, but he didn’t live to enjoy his investments. He died at, Morrisania, his family estate in the Bronx, trying to open a blockage in his urinary track with a piece of whalebone.