Hamilton’s Faith and Death

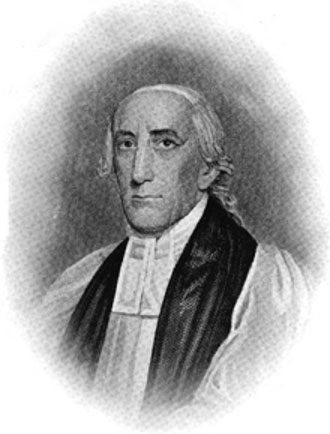

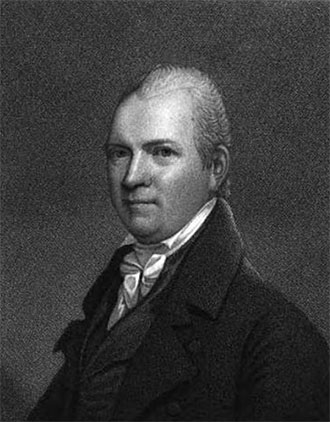

BISHOP BENJAMIN MOORE

As an illegitimate son of a “fallen” woman, Alexander Hamilton must have been sensitive to the chill of pious church goers. His presumed father, an itinerant merchant, left the family when he was ten. His mother died three years later. Young Hamilton keenly felt the sting of organized religion when his mother was denied a church burial because she was “stained.” Only thirteen, Hamilton worked as a clerk along the docks in St. Croix, dealing with crusty old sea captains and slavers.

Despite some disdain for organized religion, Hamilton was always a believer. As a boy in the Caribbean, he was befriended by Hugh Knox, a Presbyterian minister and journalist, who published Hamilton’s well-written account of a fierce tropical hurricane. Under Knox’s guidance, Hamilton also wrote religious poetry and with his mentor spear-heading the drive, islanders contributed to a fund to send the precocious boy to New York.

Hamilton graduated from Kings College (Columbia University today) which then had mandatory chapel attendance, so we know that he prayed morning and night. While Hamilton never lost his personal piety, in this age of war and revolution he embraced “deism” instead of organized religion. Deists believe that God created the world but they reject the idea that God intervenes in earthly affairs. Once God created the natural world, they believe, He left it to operate according to natural law.

Hamilton feared religious fanaticism as a threat to the new nation, but he saw that personal liberties like freedom of religion would lure manufacturers and laborers to America. Although he rented a pew at Trinity Church where his pious wife Eliza regularly attended services, and their children were all baptized Christians, Hamilton rarely worshipped with her. He did provide free legal services to the church, and his outwardly pious disposition contrasted with Thomas Jefferson’s suspected atheism.

As a young orphan in a port town with a thriving slave market, Hamilton saw cruelty at an early age. When the Reign of Terror swept through France, Hamilton again saw man’s inhumanity to man. The French Revolution luridly demonstrated how men hungry for power became beasts who guillotined hundreds of men and women per week under the guise of overthrowing tyranny. In light of the massacres, the Jacobins’ purported “reason” and their “liberty, equality and fraternity” were thin facades to hide the dog-eat-dog envy and violence in their hearts. Still Hamilton believed in a natural human impulse toward God, and in his later years hypothesized it was the basis for all law and morality.

After he was mortally wounded and lay on his deathbed, Hamilton’s religious yearnings surfaced. Some considered this a “deathbed conversion,” but I believe he was only expressing what he had always believed, that mankind could seek refuge in the belief of God’s goodness and justice and the existence of heaven. Hamilton asked to receive the sacraments, and the Episcopalian Bishop Benjamin Moore was summoned.

Moore, however, refused to give him the last rites and communion because he’d been wounded in a duel, which the church viewed as a grave sin, having elements of both murder and suicide. The mourners then sent for Rev. John Mason, a Presbyterian minister, who conversed with Hamilton about the mercy of Jesus Christ and His offer of salvation, but likewise refused to administer the last rites.

REV. JOHN MASON

Hamilton persisted. He knew he was going to die and he wanted to unburden his heart and soul by acknowledging his sins and receiving communion. Those at his bedside sent for Reverend Moore again, and this time, after satisfying himself that Hamilton’s contrition and repentance were sincere, Moore gave him communion and the last rites. When he received communion, eyewitnesses report that Hamilton sighed, “Grace, rich grace,” and all of his agitation about his condition and the farewell to his family departed as he accepted his death.

Both Moore and Mason published letters in Hamilton’s newspaper The New York Evening Post, explaining their initial refusal to give Hamilton the sacraments and the solace he sought, with Moore setting forth the reasons he relented.

Hamilton died peacefully at 2p.m., July 12, 1804. He left a grieving widow and seven young children, but his final request for religious solace and communion raised him in the esteem of his admirers.

REV. ELIPHALET NOTT

About three weeks after his death, in his wife’s childhood church in Albany, Rev. Eliphalet Nott, a Presbyterian minister, gave a eulogy for Hamilton with his wife and family in attendance:

“And is there, amid this universal wreck, nothing stable, nothing abiding, nothing immortal, on which poor, frail, dying man can fasten? Ask the hero, ask the statesman, whose wisdom you have been accustomed to revere, and he will tell you. . . . [H]is illumined spirit still whispers from the heavens, with well-known eloquence, the solemn admonition: “Mortals! hastening to the tomb, and once the companions of my pilgrimage, take warning and avoid my errors; cultivate the virtues I have recommended; choose the Savior I have chosen; live disinterestedly; live for immortality; and, would you rescue anything from final dissolution, lay it up in God. . . .”

Specifically recalling Hamilton upon his deathbed, Reverend Knott said:

“To the exclusion of every other concern, religion now claims all his thoughts. Disburdened of his sorrows, and looking up to God, he exclaims: ‘Grace, rich grace!’

’I have,’ said he, clasping his dying hands, and with faltering tongue, ‘I have a tender reliance on the mercy of God in Christ.’ In token of this reliance, and as an expression of his faith, he receives the holy sacrament; and having done this, his mind becomes tranquil and serene. Thus he remains, thoughtful indeed, but unruffled to the last, and meets death with an air of dignified composure and with an eye directed to the heavens.

This last act, more than any other, sheds glory on his character. Everything else death effaces. Religion alone abides with him on his death-bed.”